Compulsory repatriation of Chinese seamen in Liverpool

-

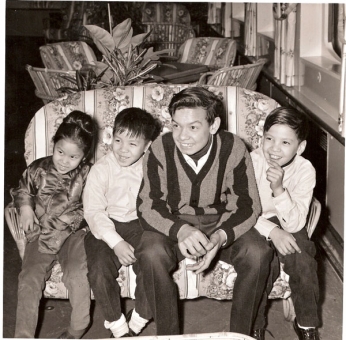

Eurasian Children Reproduced with kind permission of Yvonne Foley, www.halfandhalf.org.uk (1/4)

-

Liverpool Eurasian boys who appeared in the Ingrid Bergman film The Inn of the Sixth Happiness (1957). Reproduced with kind permission of Yvonne Foley, www.halfandhalf.org.uk (2/4)

-

Eurasian boy in China. Some Chinese fathers in Liverpool sent their eldest son back to China for their education. Reproduced with kind permission of Yvonne Foley, www.halfandhalf.org.uk (3/4)

-

Brian, one of the hundreds of children whose fathers were forcibly repatriated. Reproduced with kind permission of Yvonne Foley, www.halfandhalf.org.uk (4/4)

In the early 1940s, an estimated 20,000 Chinese merchant sailors were recruited into the British Merchant Navy and, almost entirely based in Liverpool, around 300 of these married or cohabitated with local women. Although the Chinese sailors played a vital role in Britain’s warfare, their demands for the same pay and equal treatment as local sailors in 1942, which led to strike action, saw them labelled as troublemakers. Post-war, the government, in collusion with the shipping companies, were keen to rid Liverpool of what they saw as an ‘undesirable element’ and, in October 1945, the Home Office opened a file on ‘the compulsory repatriation of undesirable Chinese seamen at Liverpool’.

As has been identified through recently released records, although many of the sailors were not reluctant to return to China given the hostile conditions in Liverpool, some of those who had families were not given an opportunity to stay, as the law prescribed. Although we do not know exactly how many Chinese seamen were deported, including those who had relationships and families with local women, it is estimated that more than 200 men with dependents were suddenly and forcefully repatriated, leaving behind distraught families who believed themselves abandoned.

The British wives of the Chinese seamen who had been repatriated formed a defence association in Liverpool to campaign for the rights of Chinese seamen’s families, though to little avail. As far as records show, there were no reviews of individual cases, or appeals. During the last half century, those left fatherless have grown into adults and (as with the children of Black GIs and British women) have sought to identify and track down their fathers. Their testimony is brought to life by photographs assembled by one of them, Yvonne Foley, who has remembered these fathers and their families in her website: www.halfandhalf.org.uk.

‘He just went out to the shop, and my mum was waiting for him to come home, and he never came.’